Macroeconomic Indicators

Despite unemployment falling from 10% to 3.9% over the course of the past eight and a half years, U.S. inflation isn’t exactly rip roaring. Core CPI, excluding volatile food and energy prices, is at 2.1%. The Federal Reserve’s preferred measure, the core PCE deflator, has risen 1.9% over the past year. While these numbers may seem a bit modest, they contrast sharply with the situation in Europe where core inflation recently fell to 0.7% YoY and hasn’t exceeded 2% since 2003 (Figure 2).

The difference in inflation stems in no small part from the very different states of the European and U.S. labor markets. U.S. unemployment recently fell to a 17-year low and is half a percent below its pre-recession level. European unemployment began falling four years after the U.S. labor market began to recover and remains at 8.5%, over a percent higher than its pre-recession level (Figure 3).

Comparing U.S. and European unemployment rates is always an arduous task. European labor laws differ much more from one country to another than U.S. labor laws differ from one state to another. As such, some European countries, notably France, Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain, have notoriously inflexible labor markets whose regulations protect workers and create, as an unintended consequence, elevated levels of structural unemployment. Many of these countries, by necessity or choice, have begun to reform their labor markets which may have the impact of lowering the level to which Europe’s unemployment rate could potentially fall without generating inflation, barring any misstep by the European Central Bank (ECB) that hinders the economy’s continued recovery. An unemployment rate of 3.9% might not be realistic in Europe, but given the low level of inflation, generous monetary support and the fact that unemployment has been falling at a pace of 1% per year, it’s easy to imagine unemployment falling below 7% by the end of the decade. Whether this would be enough to ignite inflationary pressures is another matter but it might convince the ECB to begin normalizing policy by ending quantitative easing and negative rates.

Fiscal Policy

One thing is clear: Europe can’t count on any fiscal support to boost its economic prospects in the near term. Chancellor Angela Merkel won’t allow it in Germany, the country that is in the best position to offer a stimulus. Also, no tax cuts or spending increases are on tap in President Emmanuel Macron’s France, which is mainly focused on improving labor market flexibility. Italy’s new populist government would probably like to offer fiscal stimulus but 130% government-debt-to-GDP ratio should be enough to contain any such ambitions. Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain were burned badly by the most recent financial and fiscal crisis to entertain the idea of tax cuts and spending increases.

The contrast with the U.S. couldn’t be greater. Despite being eight years into an economic recovery, Congress cut taxes in December and passed a budget-busting spending program in March. The U.S. budget deficit, which shrank from 10% to 2.2% of GDP from 2009 to 2016, was already expanding towards 3.5% of GDP in 2017 before these developments. By the end of Q1 2018, before any impact from the spending legislation had been felt, it was at 3.8% of GDP and is probably on its way to 5.0-5.5% of GDP by 2019 (Figure 4).

Generally speaking, larger budget deficits are bearish for currencies. As such, Europe’s comparative fiscal discipline should support the euro at the expense of the U.S. dollar, which has often weakened in response to past expansions in both fiscal and trade deficits (Figure 5). At the very least the combination of a shrinking Federal Reserve balance sheet and increasingly large deficits should boost the amount of U.S. debt on the market at a time when European debt remains relatively restrained amid continued (if slowed) quantitative easing and shrinking budget deficits.

Monetary Policy

Monetary policy is the most obvious area of divergence between the two currencies. On the one hand, the Fed is raising rates vigorously and promises to continue doing so even as it shrinks its balance sheet. On the other hand, the ECB continues to buy bonds and probably won’t raise rates until late next year at the earliest.

How EURUSD reacts to divergences in the U.S. versus eurozone monetary policy varies over time, (Figure 6) but the direction is always consistent: higher rate expectations in the U.S. correlate to a stronger dollar and a weaker euro. In the past year, the relationship has been unusually weak, perhaps owing to the market’s attention to the U.S. fiscal expansion and the legislation that Congress passed in December 2017 and in March this year. That said, no similar legislation will likely pass Congress during the current Administration. As such, markets will be free to concentrate on monetary policy divergence again, even as U.S. fiscal deficits grow and European fiscal gaps narrow.

The Fed’s dot plot suggests two or three additional rate hikes in 2018, followed by two or three more in 2019 and one or two more in 2020. Markets are in partial agreement. Fed Funds futures prices 2-3 additional hikes in 2018 and then one or two more in 2019 followed by an indefinite pause. The ECB won’t likely tighten policy until late 2019 at the earliest.

The focus for the ECB in 2018 is the ending of additional quantitative easing measures. In 2019, the focus will likely turn to leadership changes when ECB President Mario Draghi’s term ends in October next year. The battle over his succession will be crucial to determining whether the ECB pursues the dovish and accommodative stance it has undertaken since Draghi became leader or whether its new leadership will focus on fighting inflation, no matter how non-existent that inflation may be. In any case, it is conceivable that Draghi will try to normalize policy slightly before leaving, perhaps at least ending the ECB’s experiment with negative interest rates.

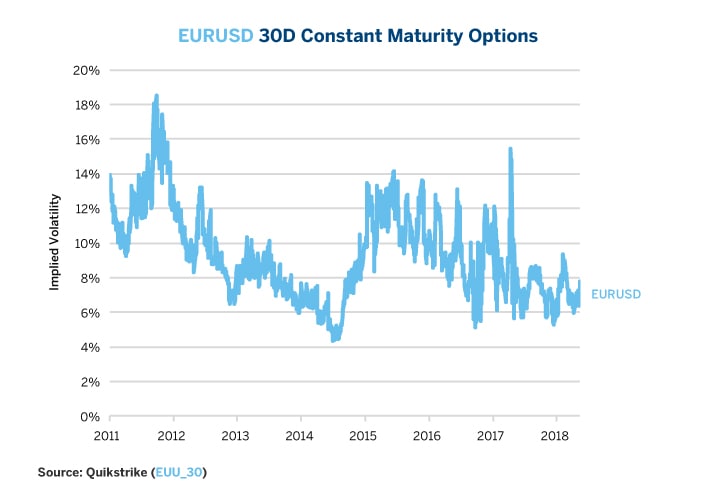

EURUSD’s trajectory depends on which set of factors, fiscal or monetary, gain the upper hand. Options prices imply that monetary policy will likely be the stronger of the two influences in the near term. EURUSD’s implied volatility skews to the downside, with options prices below the at-the-money (ATM) level priced higher than options an equivalent distance above the ATM price. This pattern holds true for a variety of different maturities (Figure 7).

There is some logic to this view. Normally, fiscal policy changes at a glacial pace. It requires a seismic event like the outcome of the 2016 U.S. Presidential election to change its course and, even then the recent tax and spending legislation cleared Congress by only the narrowest of margins. There is no reason to expect another such shock before 2020 even if party control of Congress changes after the November mid-term elections. Likewise, Europe’s fiscal state is unlikely to evolve much over the next year.

Compared to fiscal policy, monetary policy is much more flexible. Central banks often act with a great deal of inertia. Unchanged short-term rates tend to beget more unchanged short-term interest rates. Rate rises tend to lead to more rate rises. Central banks often tighten policy until something goes wrong. Occasionally, they achieve soft landings as the Fed successfully engineered in the mid-1980s and again in the mid-1990s. More often, however, they tighten until something goes wrong. In the ECB’s case, they may leave policy easy until something goes right: unemployment falls further and core inflation finally begins to make a serious approach to their 2% target – a prospect that seems far off.

As such, options traders may be right to cast their lot with the idea that monetary policy will, more likely than not, pull the dollar higher and the euro lower over the next 12 months. Where the dollar will really get into trouble will be when the U.S. economy slows and eventually falls into a recession. That would bring the fiscal and monetary factors into alignment with falling interest rates and exploding budget deficits. This scenario, however, almost certainly won’t happen in 2018 and probably won’t happen in 2019 either.

It may, however, happen in the early 2020s, depending upon how much further the Fed tightens policy and if its policy tightening inadvertently derails economic growth. The eurozone may eventually suffer the consequences of a U.S. recession but the two currencies’ economies aren’t perfectly synchronized. For example, the U.S. went into a recession in 1990 and 1991, but that storm didn’t come ashore in Europe until 1992 and 1993. European currencies rose 15-20% versus USD in 1990. Likewise, in 2007, the first signs of trouble began to appear in the U.S. subprime mortgage market about 18 months before European credit markets began their own very different sovereign debt crisis. In 2008, the euro reached its all-time high of nearly 1.60 versus USD as the U.S. economy sank while Europe appeared to avoid the crisis, at least in its early stages. As such, if the U.S. experiences a downturn in 2020 or 2021 as a result of excessive monetary tightening, a still easy ECB could prevent or delay such a reckoning in Europe for a year or two, sending the euro soaring.

Bottom Line

- Monetary and fiscal policy in opposite directions on EURUSD

- Monetary policy may win out over the next 12 months and push the dollar higher

- Options traders see more downside than upside risk to the euro

- A U.S. recession, perhaps around 2020 or 2021, could align fiscal and monetary policy and seriously weaken the U.S. dollar versus the euro early in the next decade.

All examples in this report are hypothetical interpretations of situations and are used for explanation purposes only. The views in this report reflect solely those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of CME Group or its affiliated institutions. This report and the information herein should not be considered investment advice or the results of actual market experience.

-

Recommended For You

Read original article: https://cattlemensharrison.com/euro-dollar-caught-in-a-fiscal-monetary-tug-of-war/

By: CME Group